When asked about their favorite teachers, I've mentioned before that my college students routinely say it's those instructors who cared about them as individuals. In the K-12 setting, getting to know your students can be relatively easy as you see the same students every day and are likely to have prior connections with siblings or parents. It can be challenging to get to know your individual students at the college level as you do not see them frequently and likely have no prior connection. Building positive, personal relationships with your college students takes time and effort, but putting in that little extra work is well worth the results.

The case for building relationships

We all have anecdotal and personal evidence demonstrating how teacher-student relationships affect our engagement and learning, both for the positive and the negative. Indeed, there is a whole body of research examining teacher-student relationships in schools and their effects on learning. A meta-analysis of this research demonstrates that positive teacher-student relationships lead to positive affective and cognitive outcomes. In contrast, negative relationships can interfere with students' ability to cope with school demands. Classrooms with positive relationships have students who participate, feel satisfied, and are motivated to learn. Positive teacher-student relationships also affect teachers with increased job satisfaction and reduced teacher burnout.

With forced remote learning during the pandemic, relationships between teachers and students became more individualized. Often students were working alone or in small groups online, without the modulating effect of other students in the room. Positive individual student-teacher relationships were vital for adolescents to persist in their education through the pandemic. Teachers' efforts to build and maintain positive relationships with students ultimately contributed to students' learning and their overall well-being.

So, if positive relationships contribute to teacher and student well-being and support student learning, how do we build those positive relationships with our students?

Establishing relationship boundaries

Before we consider our students, we must decide our own relationship boundaries. As teachers, we are in a position of authority and must conduct ourselves accordingly. If you've been teaching a while, you probably don't think about maintaining authority. You have the education, reputation, and demeanor that sets you a bit above your students. You can be friendly with students without losing authoritative respect.

If you are young and new to teaching, it is essential to establish your authority and decide the relationship boundaries with your students. My first teaching experience was as a graduate student teaching a small group of all-male medical students, some older than me. As a young female, I portrayed confidence in my subject knowledge and, at first, did not smile or joke with my students. As the semester wore on, my students grew to respect me, and we could relax and have fun with the learning experience. I still said "absolutely not" when asked if I wanted to join the group for a drink because I was their teacher, and that would be crossing a boundary I had set.

Even as I have gotten older and more experienced with my teaching, I have set student relationship boundaries that I do not cross. I'll joke with my students in class and stop and talk with them when I see them out in the community. I will not purposely meet students outside of class, nor will I friend them on social media. I have former students as friends on social media, but only after they graduated and sent me a request. These boundaries have worked well for me, and I plan to maintain them throughout my teaching career.

It can be easy to go too far on the authoritarian side of a teacher-student relationship, becoming the task-master giving top-down instructions and expecting students to perform. Positive relationships are a give and take. Once the roles and boundaries are set, we, as teachers, must be open to building relationships with students, making connections, and treating them as individuals.

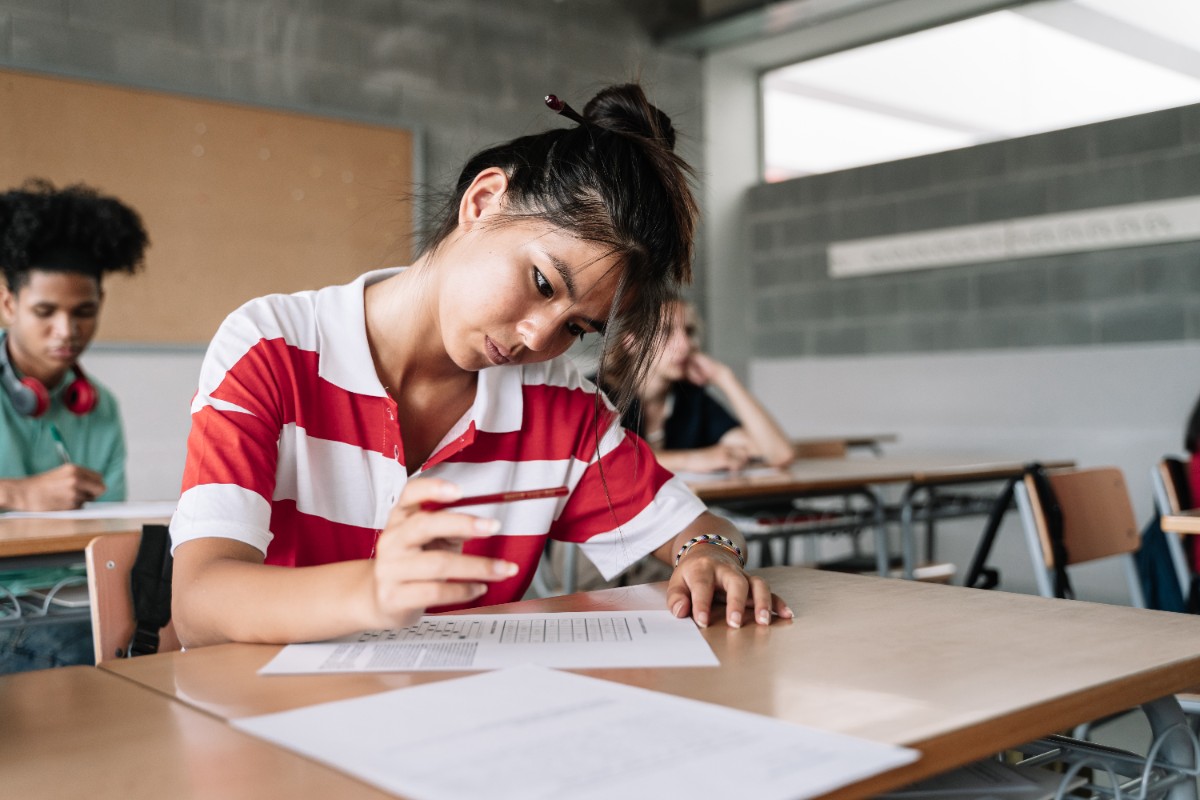

Learning students’ names

The very first thing in any relationship is learning each other's names. Students will usually know your name, but retaining their names takes time and effort.

Everyone checks out the class roster before the first day. I like to see how many students are in my class and get a sense of the general make-up of years in school and potential majors. I will not look at the provided pictures of students because they often do not look like the person, and I don't want to make unconscious judgments of a person based upon their picture. I'll print the roster from Excel with some blank columns to add notes about each student. The first and most crucial column on this sheet is the preferred name of each student.

Learning how to pronounce students' names correctly is crucial for fostering positive relationships. Even in an online format, students introduce themselves verbally. When this occurs, you can hear how they pronounce their names. I'll usually repeat their name and, if it is unfamiliar to me, I'll ask if I'm pronouncing it correctly. Students' preferred names are written on my printed roster, sometimes phonetically, so I can practice saying students' names on my own. I find the effort put into this act fosters positive relationships more than any other.

Connecting a student’s name with the physical person is another critical piece to building a relationship. This can be done with tent cards in large lecture classes, by studying pictures of students found in the roster or provided through a class activity, or with simple practice over time. A blog by Kata Dosa at the Center for Teaching and Learning at Georgia Tech shared some good anecdotal evidence of instructors' power to learn students' names. Even if you don't learn all of your students' names, there are still positive outcomes if students perceive that the instructor knows their names.

I use students' names as often as possible, not only in class but in written correspondence. When providing written feedback on critical assignments, I'll start with the student's name – as if I were writing an email. Speaking of emails, I periodically check students' progress through the semester, usually every three weeks. If a student has several missing assignments, has not logged in to the course management system, or is missing in-person classes, I'll send an email. The text starts with what I notice: "I noticed you have missing assignments." Then goes on to express concern: "I'm writing to see how you're doing." Finally, I'll express an optional next action for the student: "Let me know if you have questions or concerns about the class or assignments." Letting students know that I notice them with a personal email always results in increased engagement in the class.

Informal connections with students

You never get a second chance to make a first impression. With forced remote learning, almost every college instructor and many K-12 teachers have an online course management system that students can access before the first official class meeting. When preparing my online course materials, I establish authority by sharing the syllabus and course expectations and providing my contact information. I then have a short, informal introduction paragraph sharing my varied interests like reading, anything related to food, and exercise (so I can eat what I want). I may mention a recent trip, places I've lived, or share a picture of me with my family. Giving students information about me informally and with a bit of a sense of humor lets them know that I'm human and am willing to connect with them. Because of this introduction, I've had several conversations with students about food, books, and other topics. Having this information available lets students identify common interests and make connections with me in a way that is not forced.

In this connected world, the introduction you provide is not the only place where students can learn about you. A student recently mentioned that they looked me up online and discovered the church I attend, that I volunteer at the local food pantry garden, and that we likely live in the same town. I was a little surprised, but at least I had nothing to hide. Let this be a lesson; everyone should check their online presence periodically. After this revelation, I plan to Google myself at least twice a year - before each semester starts!

I have an active classroom. The majority of class time is spent with students working in small groups. While students work, I walk around the room listening to student conversations and sometimes interjecting with questions or comments. It is a casual atmosphere of discussion, sharing, and learning where informal talks about recent movies or music often occur. Because students know that I like books and food, I've often been involved in casual conversations about these topics. I carry a notepad and pencil wherever I go and write notes to help me remember things about the class, like who is working with whom, and about significant conversations that can help with my instruction. I may also write informal information like a common book enjoyed or a concert that will be attended. Writing down those notes helps me remember, and maybe later, I can mention it, reinforcing connections and relationships with students.

With online classes, it can be a little more challenging to get to know students. Much of the work is written, so personality and thoughts are often edited before being submitted. And, it takes more time to write than it does to speak. So, I try to use audio or video discussions when appropriate. Using VoiceThread or Flipgrid, while somewhat awkward at first, can help students share a little more about themselves. Students do tend to share more when it's only the instructor they're responding to. I had a student submit a video paper because he had recently broken his hand. In an example, he said one of his favorite shows was Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I mentioned in my feedback that it is also one of my all-time favorite shows. This little piece of information helps me remember this student's name and gives us a shared interest.

Listening to students’ needs

Above all, the best way to forge relationships with our students is to listen to them when the opportunity arises. Whether in assignment submissions, personal emails, class, or individual meetings, showing that you hear what students say strengthens relationships. Listening is a skill that takes practice, and responding to what you hear takes effort.

Listening to students supports equity in schools. Education Week published a video series last year on black student voices. Racism, sexism, classism, etc., is a result of seeing people as part of a group rather than as individuals. Listening helps us see our students as individuals first and part of a group second. It may be a challenge to connect with students who have life experiences vastly different from our own. You may find commonalities in cultural experiences with movies, music, or games. Still, it may be enough to simply listen and be open to forging a connection, even without shared experiences.

Students needing accommodations to support their learning need individual attention. Meeting with and listening to these students has helped me design my classes, making them accessible for everyone. Using video and audio in addition to text supports students with vision impairment, as does using accessible documents. Most of my assessments are open-ended projects with detailed rubrics for evaluation. Tests do not have time limits, and oral exams are an option. These and other ideas fit the concepts of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Having an accessible class helps those students needing accommodations and opens the door for all students to be successful. And it begins by listening to students' needs.

Forging positive relationships with students is beneficial for you, your students, and their learning. Set your relationship boundaries, try to learn and use your students' names, be open to finding ways to connect with your students, and above all, listen to your students. Relationships are a give and take, and we can set the stage to forge positive connections with our individual students, thereby supporting them as learners.